We delve into the reasons why there are so few women in construction and what we can do to change this.

Photo credit: The RG Group

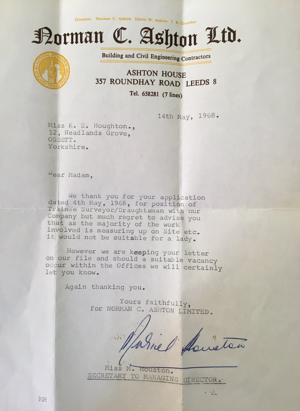

A severe skills shortage meant that women played a key role in the British construction sector during the Second World War. The rebuilding of Waterloo Bridge, often referred to as the ‘Ladies’ Bridge’, was carried out by a predominately female workforce. However, this step forward came from necessity rather than a desire for gender parity. In fact, inequality was rife at the time. The National Joint Council for the Building Industry even agreed on terms of employment for women during the conflict. Below was a feature of their restrictions.

“No man shall be discharged in order that his place may be filled by a woman; and, if at any time the Trade Union concerned can supply the Employer with male labour of the appropriate class, the number of women may be correspondingly reduced.”

Women were often only allowed to complete small parts of skilled jobs. As a result, semi-skilled men were promoted to skilful jobs ahead of women. After peace was declared, the majority of these female construction workers were ejected from their jobs despite being praised for the work they had carried out. They were directed back into domestic service, shop work, and clerical jobs. The Minister of Labour at the time refused to recruit any more women and demanded that all men under 60 with building experience register for construction work.

The passing of the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act, later replaced by the 2010 Equality Act, meant that women in Britain were protected against negative treatment on the grounds of gender. As a result, women were allowed to acquire craft skills for the first time without the patronage of a company. Employment, training, education, and harassment were just a handful of areas covered by this law.

Despite the criminalisation of the barriers that used to push women out of the sector, gender equality in the construction industry today is still behind the times. Less than 15% of those aged 16-35 would consider a role in construction, only 13% of the UK workforce are female, and one in five construction businesses in Britain have no women in senior roles.

So, what are the 21st century obstacles dissuading women from entering the industry?

Photo credit: The Ladies' Bridge

Perception

One of the most powerful barriers preventing women from applying for jobs in the construction industry is the perception of the sector. Speaking to Building Magazine, Nicola Thompson, the Construction Industry Training Board’s Communications Manager, said: “It’s interesting that when you ask people about their perception of the industry, it is rooted in the past. Girls immediately think of bricklayers and have bricklaying in mind when they answer the question.”

The truth is that there’s so many jobs in the industry, most of which do not involve physical labour, but rather a high level of academic training and attention to detail. For those carrying out manual work, brute strength is no longer needed as advancements in engineering and technology mean that machines can now shoulder the majority of the work.

Negative perceptions are perpetuated by the manner in which construction roles are advertised. They are ‘stereotypical male jobs’, often targeted at those who have struggled in society and are looking to turn their lives around. The use of gendered language in recruitment is common. For instance, a quick jobsite search brings up numerous requests for a ‘handy man’. To add to this, ‘Caution: Men Working Overhead’ signs are found on most streets in London. This use of language upholds the perception that women in construction are a minority and needs to be altered if swift progress is to be achieved.

Photo credit: The Financial Times

Sexism

A survey of 1,500 employers by The Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) revealed that 73% believe the perception of a sexist culture is a major reason why women are under-represented in the sector. Unlike the belief that women can't physically carry out construction work, the view that the sector suffers from widespread sexism is founded in truth. Removing this negative connotation is going to take a lot more than rewriting job specifications or reprinting signs.

When surveyed by The Considerate Constructors Scheme, 52% of construction professionals were found to have witnessed or experienced sexism within the industry. As part of its project ‘Building A Stronger Union’, the Union of Construction, Allied Trades, and Technicians (UCATT) spoke to female construction workers about the challenges they faced. Over half felt they were treated worse because of their gender, citing a lack of promotion opportunities, the gender pay gap, and feelings of isolation as the top reasons for job dissatisfaction. Four in ten of those surveyed believed that bullying and harassment by managers was an issue.

Stories of sexism in the industry paint a vivid picture of a hostile work environment for many women in construction. For instance, according to an anecdote featured in Building Magazine, when former Lendlease employee Megan Walters was highly commended at the Building Awards in 2005 for her campaign to better maternity rights, a bout of sniggering broke out. To add to this, when speaking to us for our What It's Really Like to be a Young Woman in the Construction Industry article, Phoebe Beatson (Quantity Surveyor at Balfour Beatty) said that she'd once been asked if she had pink work boots, in addition to being called darling and sweetheart regularly.

Moreover, women often find it challenging to secure work placements in the sector due to institutional chauvinism. There are many reports of biased recruitment processes. For instance, one 18-year-old apprentice called Sophie Browning was laughed at by a potential employer during an interview and, despite excellent recommendations, was the last student on her course to find a work placement.

Photo credit: The Mirror

Maternity Benefits

According to research carried out by The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) and the Equality and Human Rights Commission, one in nine mothers report that they have felt forced to leave their job after falling pregnant. Scaled up to the general population, this is as many as 54,000 mothers per year.

The figures for construction are more worrying than most. Employers in the sector are less likely to feel that supporting pregnant women and those on maternity leave is in the interests of their organisation. On average, 84% of employers feel that it is beneficial to them, whereas just 70% of employers in construction believe this. Construction sector employers are also more likely to believe that women should declare up front during recruitment if they are pregnant. 70% of UK businesses feel that women have a duty to disclose this, in comparison to 87% of companies in the construction industry.

Offering maternity and child care benefits is essential for employee retention and general office morale. An employee typically stays with their company for up to three years. For women who are supported through pregnancy, the average length of time can climb to seven years per child. Statutory maternity pay in the UK is paid for up to 39 weeks at 90% of the mother’s average earnings for the first six weeks and a flat rate of £145.18 per week for 33 weeks. According to 2014 figures, replacing an employee costs £30,000, therefore it is often more cost effective to support a woman through pregnancy. It also offers other employees the opportunity to take on more responsibilities while their team member is away, which can be beneficial to their career progression.

Why is it important that we encourage more women to enter the industry?

Of those working in the construction industry, 82% agree that the sector is facing a severe skills shortage. Demand is expected to require an additional million workers by 2020. The lack of engineers, in particular, is a worrying trend as there is predicted to be a shortfall of 35,000 in the UK by 2050 – a vocation crucial to the continued success of the industry.

If females were more inclined to search for jobs in construction companies, it is likely that the sector would have a workforce large enough to sustain the country like it did during the Second World War.

What are UK construction companies doing to better the situation?

Companies such as Bechtel, Tideway, and Laing O’Rourke are making headway with their women in the workplace statistics.

Bechtel’s Managing Director of Global Rail, Ailie MacAdam, is a pioneer in her own right. A visible role model to the company’s female employees, she joined Bechtel as a graduate chemical engineer in 1985 and has worked there ever since. MacAdam was named among the Top 50 Women in Engineering for 2016 by The Telegraph, and frequently advocates for women in the sector. 2017 saw the number of senior level women at the company grow by 20% and, at graduate level, women were said to make up approximately 30% of Bechtel’s US college hires, where market supply is just 18%.

Tideway, the infrastructure provider set up to finance, build, maintain, and operate the Thames Tideway Tunnel, was named a Times Top 50 Employer for Women earlier this year and Laing O’Rourke boasts multiple flexible work programmes, 26 weeks paid parental leave, Keep in Touch and Return to Work coaching schemes, and a Connecting Women network.

Click here to read more about 5 Companies Promoting Women in Construction.

How else can we inspire women to work in construction?

It's not all bad news in the sector. Despite reports of sexism, 93% of construction professionals believe that having a female boss will not negatively affect their jobs. In the same vein, 79% of female construction workers in 2005 were dissatisfied with the progression of their careers, by 2015 this number had dropped to just 29%. Here's how we can continue to push for change.

Starting With The Students

Presenting the idea that construction is a potential career choice for young girls is key to increasing the number of women in the sector. There are many campaigns aimed at school and university students that are helping to drive change.

For example, Marta de Sousa's Build by Her initiative is a brilliant scheme that helps young women build a career in construction. The campaigners visit schools and talk to 16–18 year old women. Teaming up with advertising agency Mr President, the talks run alongside a government-backed national advertising push. Brunel University London operates a Women in Engineering programme. It supports female graduates by offering them a mentor, personal professional development training, and industry visits. There's also a £10,000 Women in Engineering Award for 30 selected students.

Laing O’Rourke (also mentioned above) has also created a school engagement programme called Inspiring STEM+ designed to encourage girls to study male-dominated courses at university. Partnering with the National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC), the company has also launched the 2018 NSW NAWIC Mentoring Programme, which enables women who have recently entered the industry to connect with mentors based on age, experience, and goals.

Morgan Sindall’s female-managed project team was featured heavily in the press in 2015. This group of women led the building of St Hilda’s Church of England School in Sefton Park, Liverpool. Working closely with the school, Morgan Sindall provided female pupils with career days and other opportunities. Their work inspired many young women at the school, especially Katie Klaveness who was motivated to follow a career in construction. Morgan Sindall offered Klaveness a work placement at their £1 billion Paddington Village project, helping to bolster her university applications.

Promoting Female Role Models

The ability to reach gender parity within the construction sector lies partly with the women who have already made a name for themselves in the industry. By sharing their success stories, they are encouraging others to look at construction as a sector for women. Moreover, to avoid the predicted talent shortage, it is crucial that top construction companies in the UK actively support events that promote women in the field.

This is why the Women in Construction World Series is so important. Returning in 2019 with events in London, Amsterdam, and the USA, these conferences are a must for any women in construction looking for role models or mentors in their sector. The events feature talks from industry leaders, practical workshops, and networking opportunities, in addition to stalls where major construction companies are looking for female recruits – helping to drive change in the sector.

Click here to register for the Women in Construction Summit in 2019.

Developing Schemes And Campaigns For Women In Construction

The most important campaign pushing for change in recent years has to be the Considerate Constructors Scheme. Through monitoring registered sites, companies, and suppliers, the scheme is leading the effort to make the construction industry more inclusive. The checklist used by scheme monitors scores sites on whether they 'demonstrate a commitment to respect, fair treatment, encouragement, and support' in addition to 'providing for the needs of a diverse workforce'. When scoring the sites, inclusion, open door policies, separate welfare facilities and harassment are all taken into account.

Another forward-thinking scheme is CITB's £1 million Positive Image Campaign, which began by advertising to young people on Oxford Street. Specifically, in the changing rooms of clothes shops like Topshop and New Look. The movement also advertised on lifestyle websites, on television, and in cinemas. Building Magazine reported that CITB received 3,500 texts in the first four weeks from interested parties and 28,000 website hits.

If you learnt something from reading this article, then make sure to follow us on social media as we will be posting more exciting content very soon. Click to view our LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook pages.